August 11, 2020

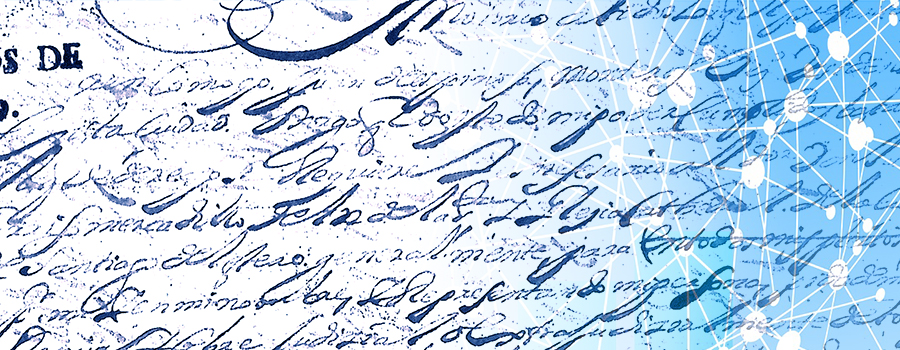

What do you do with 200,000 handwritten historical records nobody can read? Call an engineer. That’s what Viviana Grieco did when she needed help decoding a collection of 17th Century notary records from Argentina. Now, she and Praveen Rao, an associate professor of electrical engineering and computer science and health management and informatics at Mizzou, are using machine learning to translate these texts.

Grieco is an associate professor in history & Latin American and Latinx Studies at the University of Missouri-Kansas City. She and Rao received a one-year, $100,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to devise a way to decipher and digitize the collection.

Praveen Rao

“Our goal is to take this archive, which contains images of scanned, handwritten records, and make it into something meaningful for historians and students,” Rao said. “And we want to do that in a machine-driven manner.”

Although written in Spanish, the handwriting in this collection is an anomaly. Latin American script changed in the 17th Century to become more ornate. Complicating the problem is that notaries had a certain writing style that allowed them to fit more details onto one page. Letters, words and sentences weren’t well separated. And that makes it difficult to distinguish characters.

Researchers have used machine learning to translate other historical documents—primarily in Latin, French and English. But they’ve paid less attention to Spanish texts of this era.

“The 16th and 18th Century are studied more because records of the 17th Century are written in a very quirky, hard-to-understand script,” Grieco said. “The collection we are using is in the National Archives in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Right now, the scripts are only accessible to those who have extensive paleography training. We’re dealing with one of the hardest collections there is. So we’ve had to start from scratch.”

Cracking the Code

Deciphering these texts takes a human-machine relationship.

Grieco and her graduate students are finding characters they recognize and providing that data to Rao. Once Rao and his team have a large enough set, they can build a knowledge graph and a retrieval system that can enable scholars and students to identify records of interest.

Viviana Grieco

“Our first step is to take those raw images, apply deep learning and extract characters, words and sentences by building an accurate model,” Rao said. “We want to take the collection and map it to a knowledge graph that is a representation that computers can understand.”

Once they translate the records, Grieco and Rao plan to turn the current archives to searchable text other historians can access.

“We want to apply the latest technology and make a software system available on the web that anyone can search,” Rao said. “Think of it as Google for the historical collection.”

‘A Gold Mine’

For historians, this collection contains a treasure trove of information about 17th Century Latin America.

“Every expedition sent to the Americas by Spain had a notary,” Grieco said. “They left a lot of fantastic records that are very crucial for understanding certain aspects of society. These contracts tell us a lot about commerce, trade, family issues, gender history. Notary documents are widely used in all time periods. So if you have them, they’re gold mines.”

The software will also open the door for machine learning to translate other documents from that time.

“If we crack the code—which we are doing—then whatever system we have can be applied to similar collections all throughout the Americas,” she said.

The project is also advancing computer science by pushing the limits of machine learning and knowledge management. And it’s preparing future computer scientists. Rao’s graduate students are doing most of the work with software and data for the project, and they’re coming up against and solving new technological problems along the way.

“We guide them, but at the end of the day, they have to sit down and build the system, and test it and evaluate it,” Rao said. “There’s a lot of work they have to put in.”

Cross-Campus Collaboration

Grieco and Rao worked together when Rao was a faculty member at UMKC. There, they received seed money to get this project started.

Rao relocated to Mizzou early this year. But the University of Missouri System’s focus on collaborative research helped keep the team together.

Rao said he hopes the project inspires more faculty in computer science and engineering to collaborate with social sciences such as history.

“I wouldn’t have thought five years ago that I would be looking at historical collections,” he said. “But when an opportunity comes to work on a fun and interesting problem, you jump on it. I think you’re going to see more of this in the future. Our UM System, as a whole, supports that.”